Weightless in the Palace

Generally, displaying art in a palace isn't all that unusual. At one time, every palace owner quite naturally presented his collection of paintings, sculptures, and assorted works of art in his residence. The pieces were mostly contemporary to the time that the palace was built and served the purpose of highlighting the owner's status. As no new palaces were built after the First World War, the custom of presenting the latest art in palaces no longer continued. From this perspective, the palaces that have since been revived as museums, art houses, and cultural centers are more accurately art institutions within the architectural structure of a palace. And as such, it is notably unique to fill the Baroque halls of sixteenth-century Schloss Pörnbach with the works of contemporary artists. Here, two worlds are colliding on the timeline – two worlds that were once interdependent. Bringing them together does not mean the artists are succumbing to the temptation of reviving the past traditions of a stately and affirmative presentation. On the contrary, the historically and politically laden space, which a palace no doubt is, becomes an experimentation site for an unusual occupation.

The exhibition title KOSMOS SEVEN thematically circumscribes this artistic expedition into uncharted territory and designates it as a path-breaking mission.

The exhibit's artists, who have worked internationally, penetrate the still-existing palace infrastructure, not just inserting their works into the architecture, but creating an altogether new one. The various artistic mediums create a multitude of layered interactions between the artworks and the venue, as well as between the past, present, and future. Here, art is fusing time and territories and ultimately generating new, surprising realms of experiences. The palace becomes a cosmos of weightless associations.

The exhibition pieces subtly – and at times directly – reflect humanity's drive for expansion and knowledge acquisition. In doing so, some expose its destructive endeavors in service of the ineluctable thirst for total knowledge. The exhibit here in the palace inevitable points to the history of grandiose behavior – missions to conquer other countries or even the world, based on the desire to expand one's own borders. Suddenly trips to the moon, exploring other planets, and futuristic visions of settling the universe start looking like insane, feverish dreams or perhaps like the evolution of a nomadic tribe with a driving possessive gene.

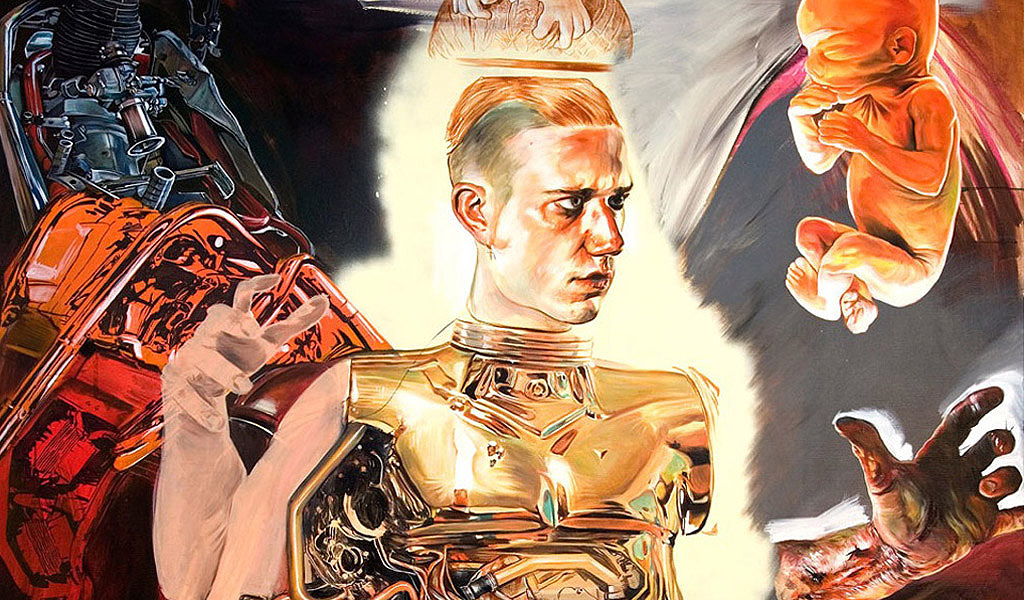

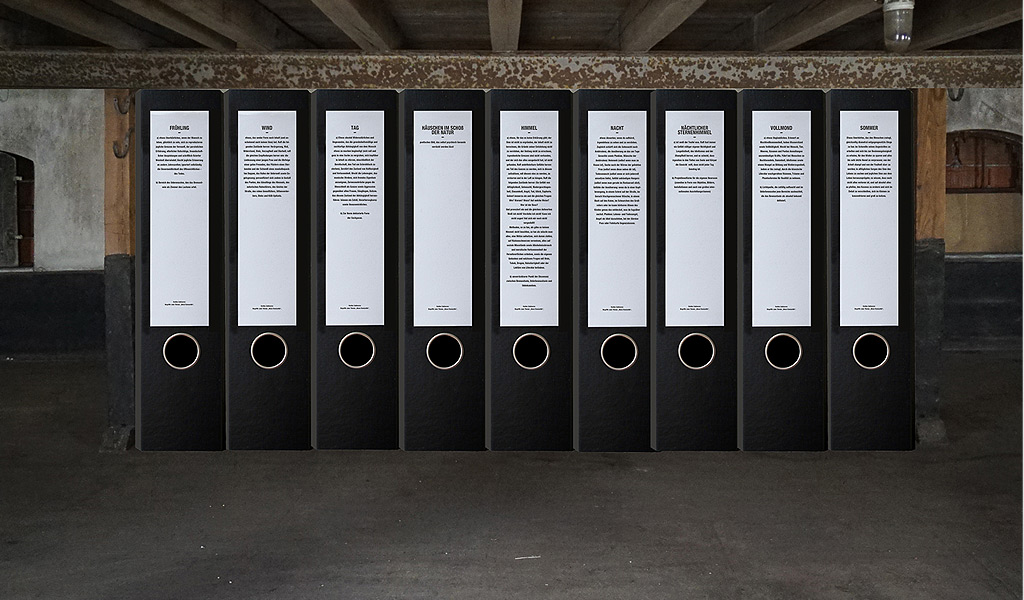

The artists put the (illusionary) worlds that society has created on display, be it the stereotypes pushed by the media in glossy magazines and the flood of images surrounding us (Peter Freitag), the history of the objects and monuments that characterize our environment (Dennis Prasolov), or the tradition of self-dramatization through art (Florence Obrecht, Avel Pahlavi). Others dissect scientific progress in man's work environment (Taisia Korotkova), or illuminate organic structures in nature in order to implant them into the social structure we know as the human being (Alexei Kostroma). And others dedicate themselves to a microcosm and artistically take over microorganisms that become frighteningly aesthetic prosthetic beings (Nicolas Darrot). Or they develop surreal worlds by creating bizarrely beautiful objects (Natalia Pivko). These manifold microcosms are reminiscent of the curiosity cabinets and Wunderkammern of the past, which even then served to spark the imagination. Many visions of past eras have become the realities of today and bring up the question which of today's visions will become the realities of tomorrow? This thought process is echoed in a sight-line between two pieces of art: photographs of nature reserves, practically unexplored macrocosmic idylls, describing a primitive state (Jasmine Rossi) are placed diagonally across from huge vitrines morphing into aggressive labs in which technology and nature are equally constructed and controlled (Anthony James). These frozen cross-sections of worlds, which one would rather not imagine colliding, could follow a concept of calculated instructions archiving numerous individual dynamics as disruptive factors in the future (Vadim Zakharov). Despite their discrepancies, these works function as a parameter for the spectrum of artistic reflections in this exhibition.

There is no plural for cosmos, but also no clear definition. The artists are free to narrow in on this original dimension of being either pluralistically or diversely. They touch on the overwhelmingness, the timeless fears, the visions that will not stop, the pull and temptation, as well as the beauty, and the natural aesthetic, that this fascinating abstract concept triggers in us. Humans and nature are the points of reference here, interwoven, as becomes clear in many of the works. Each individual thing and each individual being, however, creates a microcosm, and to experience this requires us to first experience the world at large, the macrocosm.

The title has been augmented with the symbolic number seven. As a transcendental number, it seems to strive to increase the power of the scientific term "cosmos" in its connotations of endlessness and creation. Starting with the initial seven visible planets, it had its place in the early explorations of space. Usually the mystical number seven predicts positive outcomes of expectations. In almost all religions, cultures, and especially fairy tales, it is considered to be exceptionally meaningful. It points to a world of storied tales, of fantasies, as well as to metaphysical perceptions or the perceptions of children, which, due to their deeper meaning, have to this day not lost their power. In fairy tales, the sevens are always saved and always have something to eat.

Constanze Musterer